Yesterday, 29th

January 2014,

the Centre was pleased to welcome Dr. Gareth Davies

(St. Annes College, Oxford University) to the seventh of the Centre’s 2013-2014

seminar series. In what was a truly thought-provoking lecture, Dr. Davies discussed ‘Taming Disaster:

Fatalism and Mastery in American Disaster Management, 1800-2013.’ Below is this

listener’s brief summary of the lecture.

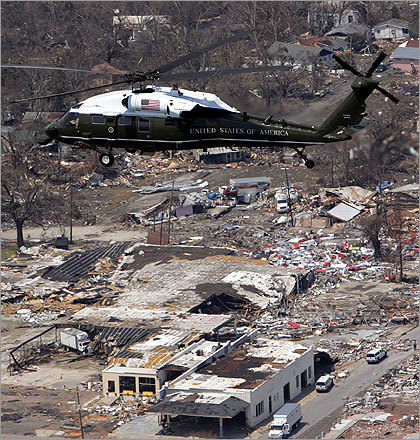

Marine One above the decimated city of New

Orleans following Hurricane Katrina, 2005

When President George W. Bush flew over flood-ravaged

New Orleans immediately after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, opting not to

land for a closer look, it fuelled public sentiment that his administration was

not being proactive in the disaster that had taken lives and destroyed so much

property. Bush acknowledged as much in his memoirs. Indeed, as Hurricane Sandy in 2012 illuminated, when

both presidential candidates effectively had to cancel planned campaign stops

and all eyes pivoted to how President Barack Obama would respond, Presidential visits matter in times

of disasters. But has this always been the case? Has it always been the federal

government’s responsibility to react with all the resources at its disposal

when natural disasters strike?

According to Dr. Gareth Davies in his ‘Taming Disaster’

talk, the answer is no. In the Early American Republic there were very few

tools to draw from to combat catastrophe and the lack of communications and

governmental structures meant that response was limited. For example, in the

1811-12 Missouri Earthquakes, which remain the most powerful earthquakes to hit

the eastern United States in recorded history, territories were decimated and

the extreme ruralness of these rugged frontier lands meant that word of it got

out slowly. There was no expectation of governmental assistance at the

time but rather it was religious groups, believing these disasters to be the

work of God, who would raise money and assist when they could.

After the Civil War, the federal government began to

take a larger role in disaster prevention and assistance, but the expectation

was still on local organisations and philanthropic efforts. Thus, the government

played a role as part of a massive national collective, with the growth in

newspapers raising awareness and the strides in technology improving prevention

tools. By the Progressive Era, people began to

turn to local governments to respond. For example, following the 1900

Galveston, Texas hurricane that destroyed one third of the property in the area,

many people were dissatisfied with the way local governments responded, but

people did not turn to the federal government or the president. Instead, the

hurricane triggered the mobilization of an important movement to reform local

government since it was viewed as the locus of response. The Red Cross too

increased its role, playing a massive part in assisting those affected by the

1927 Mississippi floods.

So then, when did the people start

looking to the President to provide leadership in response to disasters? Although

President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal initiatives begin to bureaucratise the

nature of disaster prevention and response, even President Dwight Eisenhower

did not visit the Louisiana coast in 1957 when Hurricane Audrey wreaked havoc,

killing some 500 people, nor did he feel compelled to do so. As Dr. Davies

argued, it was during the Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon presidencies that the

decisive change took place.

Accordingly,

one of the key turning points in expectations that the President respond to

disaster was following Hurricane Betsy in September 1965. Although initially

disinclined to visit the site, but eventually persuaded to do so based on

political considerations by Louisiana Senator Russell Long, who had recently become

the Senate Majority Whip, President Johnson’s response was unprecedented. Betsy

was a Category 4 storm with wind gusts near 160 mph that came ashore on

September 9, 1965. New Orleans was hit with 110 mph winds, a storm surge around

10 feet, and heavy rain. After the storm passed, Senator Long called Johnson

and urged him to tour the devastated areas. Long told Johnson of the severe

damaged done to his own home that had nearly killed his family. Johnson, along

with the heads of the Office of Emergency Planning, the Army Corps of

Engineers, the Small Business Administration, the Department of Agriculture,

and the Surgeon General, arrived in New Orleans five hours after talking to Long.

After seeing the dreadful suffering and damage from his plane, Johnson said

upon arrival, ‘I am here because I want to see with my own eyes what the

unhappy alliance of wind and water have done to this land and its good people.’

Indeed,

within hours of Betsy, Johnson was in the

city, making surprise visits to shelters, offering encouragements to the city’s

newly homeless residents, saying:

Today at 3 o’clock

when Senator Long and Congressman Boggs and Congressman Willis called me on

behalf of the entire Louisiana delegation, I put aside all the problems on my

desk to come to Louisiana as soon as I could. I have observed from flying over

your city how great the catastrophe is that you have experienced. Human

suffering and physical damage are measureless. I’m here this evening to pledge

to you the full resources of the federal government to Louisiana to help repair

as best we can the injury that has been done by nature.

As

Dr. Davies highlighted (with a rather spot on attempt at LBJ’s voice), when

making one particular visit, and by illuminating his face with a flashlight, Johnson

told the audience, ‘I’m your president and I’m here to help.’

Dr.

Davies argued that although Johnson’s response to Betsy probably did not

significantly affect the expectations that Americans in general had of

presidential disaster leadership, it did set significant precedents including

the allocation of federal funds to relieve individual disaster victims and a

massive, federally funded hurricane defence system for New Orleans. Both

measures were included in the ‘Betsy Bill’ drafted by the Louisiana delegation

following the disaster, which likely would not have passed without Johnson’s

backing. Dr. Davies then drew an interesting parallel between Johnson’s response

to Betsy and George W. Bush’s response to Hurricane Katrina – which Bush admits

in his autobiography was severely lacking in comparison. Here is an insightful op-ed about ‘LBJ’s

political hurricane’ from the NY Times.[1]

Moreover, Dr. Davies demonstrated that amidst the height of the presidential campaign in

1972, Richard Nixon was sharply criticised for his response to Hurricane Agnes

that affected numerous eastern states, particularly Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania

Democratic Governor Milton Shapp, Democratic Presidential Candidate George McGovern

and others seized on the opportunity to criticise Nixon for what they called

the government’s incompetent response. Nixon moved quickly to mitigate the

damage, but was only able to do so when he took the reins and choreographed the

government’s response from the White House. With this politicisation of the

government’s response, the President had now effectively become the ‘Responder-in-Chief.’

This expectation of presidential response has only increased

with time, and ultimately can have an adverse effect on a president’s image depending

on how he reacts. For example, in 1992, when Hurricane Andrew devastated parts

of Florida, Democratic presidential candidate Bill Clinton toured the most

devastated portions of Florida, getting media coverage as he hugged and shared

tears with people made homeless by the storm. President George H.W. Bush

visited, as well, though media reports said Bush didn't come close to

displaying the 'feel your pain' empathy Clinton did. Here

then, one is able to see an example of the importance and development in the politics of disaster

response over time.

Throughout his talk, Dr. Davies used the changing responses

to natural disasters over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries

to explore how, why, and when American expectations of government have grown,

ending by highlighting that the President’s

role as ‘Responder-in-Chief’ has only really assumed grand proportions in the

modern presidency. By interweaving both politics and natural

disasters, Dr. Davies’ work represents the best form of historical enquiry, and

the ability to use natural disasters as a way to unveil a narrative on the

changing nature of the federal government is both illuminating and intriguing.

With Dr. Davies currently turning this research into a book, the finished

product is bound to be nothing but fascinating.

By Joe Ryan-Hume

PGR at the University of Glasgow

The Centre’s seminar series continues

with Dr. Eithne Quinn (University of Manchester) ‘In the Heat of the Night (Norman

Jewison, 1967) and Racial Politics in Post-Civil Rights Act Hollywood.’ This will be held on Wednesday 12th February

2014 in Room 208, 2 University Gardens, at 5:15pm. All

very welcome!